Book Reviews plus Interview with Rob Salkowitz

In this week’s Unshelved Book Club you’ll find books about a young nerd in Philadelphia, a child made of snow who comes to life, the aftermath of cataclysmic solar flares, white bread, the sequel to Drive, a little girl hunting giants, a cape that grants super powers to a man who shouldn’t have them, and, of course, knitting.

There’s also a review of a book about Comic-Con and pop culture by Rob Salkowitz. In addition to writing about digital media and the digital generation, Rob is a futurist, teaches at the University of Washington, and directs strategy and content for Mediaplant. Rob will be on two panels I’m going to try to see at New York Comic Con next week: Digital Price Shakedown (Friday Oct 12 @ 1:30pm) and Comicpreneurs: Secrets of Successful Pop Culture Startups (Sunday Oct 14 @ 1:15pm). You’re also invited to see Bill and me (Thursday Oct 11 @ 12pm).

I had a chance to talk to Rob a few weeks ago about the business of comics and the future of media. I gauged his inner geek, discussed transmedia (and the role of librarians in dealing with it), and had him sign my galley of his book so I have yet another collectible in my basement.

Gene: I want you to start by laying out your geek cred for me.

Rob: I was always a comic book reader as a kid. My dad one time brought home a copy of Will Eisner’s The Spirit Magazine which was being reprinted at that time. I was about six years old and my dad’s philosophy was if you’re going to read comics you might as well read good comics. He remembered The Spirit from being in the newspaper. Of course, it doesn’t get any better.

So I became enamored with the whole form of comics. My first published writing was a letter that I wrote to The Spirit Magazine in 1980 when I was twelve. And the publisher who ran that letter in the magazine was Dennis Kitchen, because it was being published by Kitchen Sink at that time. Thirty-five years, when I wrote my book, my literary agent is Dennis Kitchen. He’s a great guy and a significant person in the industry. It’s very cool to get to deal with him. He’s also a very smart business guy, so he’s a good guy to have on your side.

G: I grew up reading Megaton Man, which I think he published. It was the first goofy superhero comic I ever saw. And I really liked the book he published by his daughter, Comics Is Easy.

R: As a kid I took a hiatus from comics coinciding with the period where I discovered girls and then got back into it in the mid 90s when I was doing a lot of stuff around multimedia and realized that whatever facility I had for combining words and pictures in the digital realm actually came from this experience of reading comics. So I’m a firm believer that there’s something about the medium of comics that conditions our minds to read certain kinds of narratives that have become very prevalent in this transmedia age and that as we get into this era of convergence and stuff that I focus on professionally the skills of comics reading and comics creating are going to occupy a central role in the communications strategy of the 21st Century. That’s part of what informs the book.

But I’ve been going to Comic-Con for all these years and Dennis finally said, “Look, you’re a business futurist, you’re writing all this highfaluting stuff about entrepreneurs and technology and everything, why don’t you look into your crystal ball and tell us what’s ahead for comics?” I said I’d write it if he could get it published.

G: You mentioned transmedia already, which is a word I learned in your book. Can you give me a thirty second spiel for what transmedia is.

Rob: Transmedia is storytelling across multiple formats and platforms. For example a book that gets made into a movie that gets made into a video game. But what distinguishes it from cross-platform licensing or any of these other business buzzwords is that there is elements of the story that are only present in one medium or another and you need the whole view to complete the story.

A great example of this is the Star Trek movie that J.J. Abrams did, the reboot. IDW did a comic series concurrent with the release of the movie that told the backstory of how that Romulan Captain came to his anger about Spock. You didn’t need to read the comic to enjoy the movie and you didn’t need the movie to enjoy the comic but if you had them both together you got a picture of the story and a richness to it that wasn’t prevalent in one or the other.

That’s what transmedia is.

I think IDW is really sophisticated about the way it’s participating with other media and dealing with licensed properties. They and Dark Horse are the best at that of [the comics publishers]. Dark Horse’s Buffy series that picks up from from the TV show, it’s in cannon because it’s done by Joss Whedon. A lot of these things are playing off each other and turning comics into bigger business than they used to be.

G: I walk around Comic-Con and there’s the business side of my brain that’s looking at ideas and figuring out what I can do. But I also have the collector mentality where I’m running around trying to buy things I must have. I feel like you have both of those things but you also have some layer I don’t understand. Can you explain to me what, as you’re walking around in the chaos of Comic-Con, what you’re seeing that the rest of us aren’t because of what you do for a living?

R: In the book I talk about this idea of having a framework for the future and that being in the business of being a futurist or somebody that’s looking at trends, one of the biggest mistakes you can make is saying there’s one future that we’re heading towards and start gathering information to support your prejudice about that. The way I tend to look at things is that there are multiple possible scenarios and that there are certain fundamental things that we can’t know, that are fundamentally uncertain in what we’re looking at. So to me when I look at, for example, the way comics are being produced, on one hand you see that comics are being monopolized at the top end of the industry by Marvel which is now owned by Disney, by DC which is now owned by Warner, these are two of the largest communication companies on Earth, they own everything. They own the means of production, they own the channels for distribution, they own the intellectual property. So you can say that consolidation is in the cards and that’s what I’m looking for. But at the same time you look at the bottom end of the industry and you see kickstarter and you see independently published digital comics that are topping the amazon download list and you’re seeing things like The Walking Dead which is a creator-owned property that has made the transmedia grand slam or even more off-the-wall something like Axe Cop which comes out of the mind of a five-year-old kid and his brother and is now going to be a Saturday morning cartoon series. Or maybe it’s a late night TV series. But it’s been optioned. So you see that the future is definitely bottom-up.

The thing is, from where we’re standing now, you can’t tell. So you have to segregate it out. And then you look at Comic-Con and you think, as someone who has been going for a long time, we’ve seen it go from this geek festival of 30,000 or 40,000 hardcore people to this pop culture singularity that’s taken over everything. Well, on one hand you say the trajectory is on the rise, it just keeps getting bigger and bigger. On the other hand you say all things must pass and what happens if we get over peak geek and turn into something else.

What this gives you instead of one sure vision of the future is this spectrum of possibilities. So if you use that quadrant chart [in the book] as a compass, you can walk around and gather evidence for each of these four scenarios. I think that’s a little bit different from someone who has preconceived notions or no preconceived notions and just processes everything as sensory overload. You sort of look at stuff and say okay, this is evidence for a bottom-up expanding global future. For example: self-published comics. I saw a great self-published thing out of Mexico. I’m very keen on Mexico as a center for new creative economy entrepreneurship. So, wow, this is exhibit A for that. And on the other hand you see some totally bogus manufactured property where they’re stretching like hell to create some connection to geek culture and to me that’s evidence of a completely different future than that.

That’s what the book is about, trying to process those signals.

G: I love how you bring everything together in four scenarios and show that the future pivots on two axes. It was great for me because I’ve never made it all the way through a business book before. So thank you. It was fascinating to me, too, having been at Comic-Con 2011, having your day-by-day experience and [your wife] Eunice’s day-by-day experience and talking about what it’s like on the ground is one part of the narrative. But also talking about what you saw. I didn’t realize you were fitting everything into four quadrants until at the end when you explained to me what you’d been seeing. It was great to travel in your shoes and then to get the analysis at the end.

I was thinking about libraries when I was reading your book. I think part of the challenge is going to be for libraries to figure out a way to link the transmedia together, to make it obvious that these things are different parts of the same story when that’s the case.

R: This is a challenge for librarians. And this is something where it’s going to take the skill of a librarian to solve this problem. The big challenge for transmedia is transmedia search. If you go into the iTunes store, for example, and search for Spider-man, you’ll find all of these disparate things and you don’t know what’s linked together thematically. As we know as comics fans there’s not one Spider-man, there are hundreds of different or thousands of different variations depending on who the creator is and the audience is. And for an outside to try to parse how these things fit together it’s like, wait a minute, Spider-man has a different identity in this comic than he does in the animated show that I watch. What sense does that make? So actually being able to trace the breadcrumbs through these properties to come up with a coding system and a way for readers to make sense of this. The companies aren’t going to do this. They’re just going to throw it against the wall and see what sticks. It’s somebody who has a disciplined approach to knowledge management — librarians --- that are going to solve this for us.

G: It’s funny. I’d think companies would have a vested interest in this, but all they do is put a volume number on a book.

Rob and I then talked about different superhero universes for a bit and how confusing it can be to anyone who’s not soaking in it. If you’re a geek, you’d already know what we’re talking about. But if you’re not, I’d need to write you another essay to explain it. But Rob brought it all back around to librarians:

R: Because there’s a fan base for comics, a lot of this is self-organizing. The publishers will put this stuff out there and then it’s the fans who build the archives. But it’s informal, it’s not institutional, it’s not systematic. To get a librarian discipline focused on that would be an interesting frontier for the profession.

If you need to hear Rob talk a little more about comics, check out his Tedx talk.

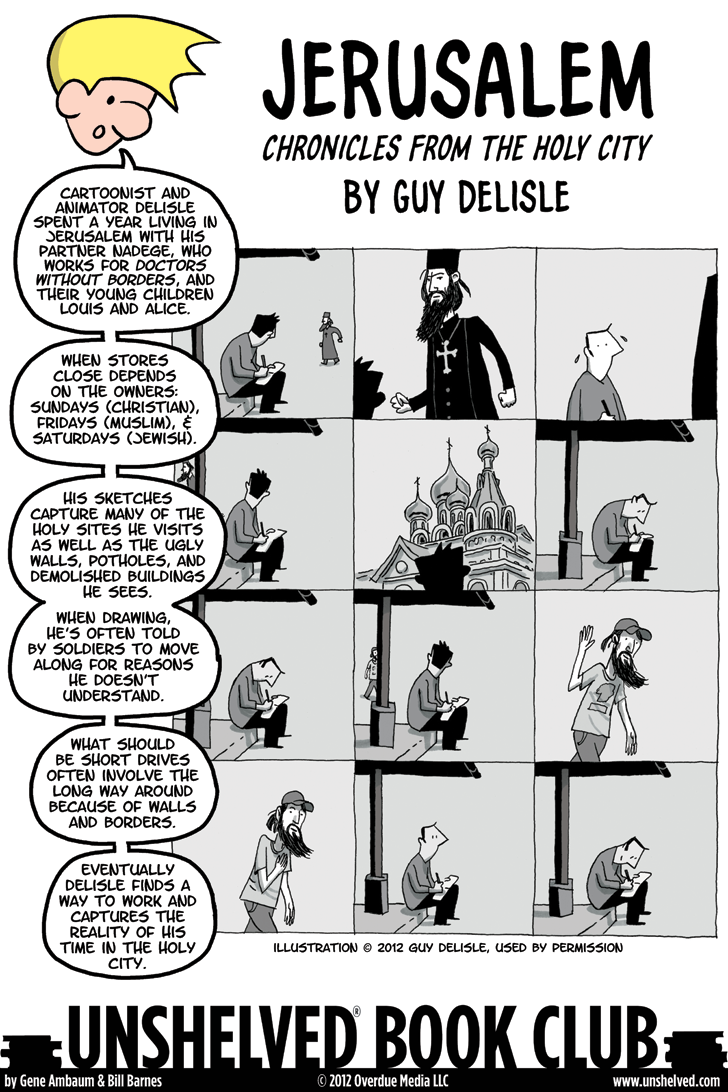

This Unshelved strip

can be shared with this link.